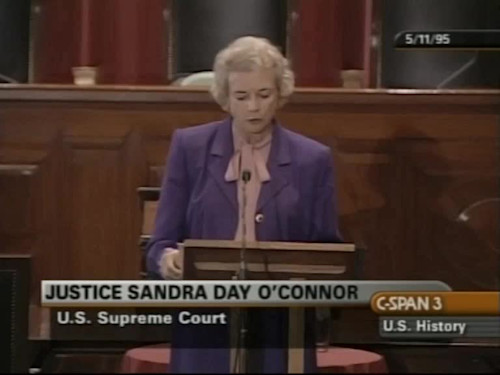

By Justice Sandra Day O'Connor

Speech on the participation of U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson in the Nuremberg Trials after World War II

May 11, 1995

DISCLAIMER: This text has been transcribed automatically and may contain substantial inaccuracies due to the limitations of automatic transcription technology. This transcript is intended only to make the content of this document more easily discoverable and searchable. If you would like to quote the exact text of this document in any piece of work or research, please view the original using the link above and gather your quote directly from the source. The Sandra Day O'Connor Institute does not warrant, represent, or guarantee in any way that the text below is accurate.

Transcript

(Automatically generated)

Unknown Speaker

Thank you.

Sandra Day O'Connor [automatically transcribed, may contain inaccuracies]

Welcome all of you. It feels a little odd to me to be on this side of that bench. But here I am, and very happy to be here for this most interesting topic tonight. And I would like to say a special thank you to Leon Silverman for his marvelous work as president of the Supreme Court Historical Society. He's really been he has spent so much time and effort on it. I think it's really worthwhile and I'm constantly grateful for all that he's done. This series, of course, commemorates the 50th anniversary of the end of World War Two and like every other instance Tuition in our country, the Supreme Court was affected by the war. And unlike everyone else in the country at the time, Supreme Court justices were involved in the war effort. There is an exhibit on the ground floor that illustrates some of that. But today we focus our attention on the very direct involvement of justice Robert Jackson, who took leave as a sitting justice in order to serve as the United States chief counsel to the Nuremberg trials. From my perspective, I think the most remarkable aspect of justice jackson, the service and Nuremberg is that he did it at all. The very idea of an independent judiciary would seem to require that justice is fully discharged their judicial function, and only their judicial function file a member of the court, but I have to admit that the practice of justices Setting political appointments and undertaking non judicial duties has an historical pedigree. During the Federalist period, Justice has quite often held other government posts and very openly engaged in political activities. Oliver Ellsworth was for 18 months both Chief Justice and our minister to France. JOHN Marshall was both Chief Justice and for a brief period Secretary of State. JOHN J. While serving as Chief Justice of this court, also ran for governor of New York was Secretary of State for six months and was ambassador to England for over a year. But such judicious involvement in political affairs was not greeted warmly in all corners. The confirmation hearings of both JA and Ellsworth were quite heated with claims impropriety and unconstitutionality and the wisdom of that criticism was sometimes confirmed by the justices themselves. After he chaired the inquiry into the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Justice Owen Roberts proposed that the chief justice or any Associate Justice or any Judge of any other Court of the United States, shall not during his term of office, hold any other governmental or public office so position. I feel he said that would be a great protection to the court. Chief Justice Harlan Fisk stone, who was Chief Justice at the time of justice Jackson's dispatched a Norenberg agreed with this view. He wrote to a friend that it has been a long tradition of our court that its members do not serve on committees or perform other services, not having a direct relationship to the work of the court. So the chief justice was not very happy for Joe distracts, and I accepted the Nuremberg appointment, Justice Frankfurt or later we call that stone beast about a lot. You know, a man on the Supreme Court should never do anything else. I guess justice Frankfurter would say that a woman on the court likewise should never do anything else. And I agree with being after justice jackson service, of course, Chief Justice Earl Warren did undertake to chair the inquiry into President Kennedy's assassination. So, once again, we had an example of that kind of service. Now,

whatever doubts the Nuremberg Trials engendered, they certainly fulfill justice Jackson's promise in his powerful opening statement of those proceedings, that the trials would be the most significant tributes that power has power ever has paid to reason. And the legacy of those trials is very much evident today 50 years later, as we see the initiation of tribunal's established to adjudicate war crimes and the former Yugoslavia and in Rwanda, so the topic is very timely indeed. And it will serve us well to reflect on the lessons of the Nuremberg proceedings. The capable person here to guide us through those lessons is Dennis Hutchinson. Professor Hutchinson teaches at the University of Chicago Law School. He hails from Colorado and was a law clerk to that wonderful justice from Colorado justice Byron white, and he also served as law clerk to Justice William O. Douglas. There aren't many who have the privilege of to such a clerkships. His academic credentials are extensive and impressive, as are his numerous publications. He is writing a biography of justice white, which I look forward to seeing one of these days. And he has written often about the Supreme Court and several of his justices. He is praised as a superb teacher, lecturer, and scholar, and it's my privilege to get him to this podium tonight to discuss this topic with us. Thank you