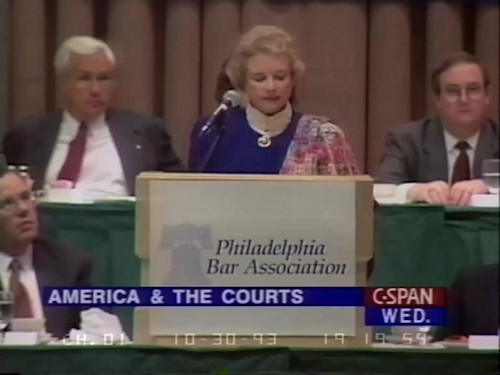

By Justice Sandra Day O'Connor

Speech to Philadelphia Bar Association

October 27, 1993

DISCLAIMER: This text has been transcribed automatically and may contain substantial inaccuracies due to the limitations of automatic transcription technology. This transcript is intended only to make the content of this document more easily discoverable and searchable. If you would like to quote the exact text of this document in any piece of work or research, please view the original using the link above and gather your quote directly from the source. The Sandra Day O'Connor Institute does not warrant, represent, or guarantee in any way that the text below is accurate.

Transcript

(Automatically generated)

Sandra Day O'Connor [automatically transcribed, may contain inaccuracies]

Thank you. Thank you so much. Thank you. Thank you, Chancellor Dennis, for a very warm introduction. And all of you are getting your exercise jumping up and down and judge the Pyro, whom I'm so thrilled to be here to honor today. And Chief Judge, slow vector and Chief Justice nicks and other wonderful and distinguished judges and citizens and lawyers and members and friends of this Philadelphia Bar Association. This is really a special day, even for a cowgirl from from Arizona. And I'm so very honored that you have decided to establish a Sandra Day O'Connor award. I'm honored that you chose to give this award my name. And more importantly, I'm delighted that you have taken the opportunity to recognize the significant accomplishments of women in the law with the publication of this marvelous book with the initiation of this award, and especially to recognize those women who like judge Shapiro have advocated the Advancement of Women in the profession, and the community and who have a reputation for being mentors to other women. Historically, encourage men or women to pursue careers and the legal profession was rare in the early part of the century, called Columbia Law School committee member George Templeton strong, wrote in his diary application from three infatuated young women to Columbia Law School. No woman shall degrade herself by practicing law in New York, especially if I can save her. Most of the early women legal pioneers faced a profession in a society that espoused what has been called the cult of domesticity of view that women were by nature different from men. Women were said to be fitted for motherhood and homelife compassionate, selfless, gentle, moral and pure. Their minds were attuned to art and religion, not logic. Man, on the other hand, were fitted by nature for competition and intellectual discovery in the world. Battle hardened shrewd, authoritative and tough minded women were thought to be all qualified for adversarial litigation, because it required logic and shrewd negotiation, as well as exposure to the unjust and the immoral. In 1875, the Wisconsin Supreme Court told Lavinia Goodell that she could not be admitted to their state bar. The Chief Justice there declared that the practice of law was unfit for the female character, who expose women to the brutal, repulsive and obscene events of courtroom life, he said, would shock man's reverence for womanhood and relax the public sense of decency? In a similar case, Myra Bradwell of Chicago who had studied law under her lawyer husband, applied to the Illinois bar in 1869, and was refused admission. The Illinois Supreme Court reason that as a married woman, her country tracks were not binding, and contracts were the essence of an attorney client relationship. The court also proclaim that God designed the sexes to occupy different spheres of action, and it belonged to a man to make apply and execute the laws. The United States Supreme Court of course, I blush to admit, agreed the Illinois court. Even Clarence Darrow, one of the most famous champions of unpopular causes his report to upset this to a group of women lawyers. You can't be shining lights at the bar because you're too kind. You can never be Corporation lawyers because you're not cold blooded. You have not a high grade of intellect, I doubt you can ever make a living. Another male attorney of the same period comment had a woman can't keep a secret and for that reason. For that reason, if no other I doubt if anybody will ever consult a woman lawyer.

Luckily, for us, women lawyers today, our female predecessors had far more spunk spirit, and then they were given credit for Clara Foltz.

Clara Shortridge Foltz the first woman lawyer in California, and the first woman Deputy District Attorney in America, displayed the characteristic metal of those early women lawyers. When an opposing lawyer once suggested in open court that she would better be at home raising children, Foltz retorted, "A woman had better be in almost any business than raising such men such as you."

A New York woman lawyer pioneer, Bella Lockwood was in 1870, the first woman admitted to practice before the United States Supreme Court to receive that honor. However, she had to try three times to get a special bill passed and the senate changing the admission requirements, inexhaustible. She wrote her three wheel all over Washington, DC, lobbying senators and explaining to the press that she was going to get up a fight all along the line in 1884, she even ran for president, reasoning that even though women couldn't vote, there was nothing to stop them from running for office. And even without women voters, she got 4149 votes in that election. Pennsylvania, I regret to say did not make it particularly easy for women to join the profession. Carrie Burnham Kilgore, who's noted in the yellow booklet here was the first woman to be admitted to the Pennsylvania bar and 1986. After numerous legislative and judicial battles beginning in 1870. As one of the first women in the country to ask for admission to the bar. She was one of the last of her peers to get it. and Mrs. Kilgore remained the only practicing woman lawyer in Philadelphia until well after the the turn of the century. Mrs. Kilgore is reported as saying in 1890, that she regrets that no other women are practicing and Philadelphia, and says she would like to have a lady student in her office and would give such a woman a chance with her after admission to the bar. Well, in my own time and my own life, I've witnessed a revolution in the legal profession. That has resulted in women representing nearly 30% of the lawyers in the country, and over 40% of law school graduates. Women today are not only well represented and law firms, but they're gradually attaining other positions of legal power, representing 7.4% of the judges 25% of us attorneys 14% of state prosecutors 18% of state legislators 17% state executives 14% of mayors and city council members 6% of Congress, and as of this year, just over 22% of US Supreme Court justices.

Well, this progress has been due in large part to the explosion of the myth of the true woman. through the efforts of real women and the insights of real men. released from some of those early prejudices, women have proved that they can do a man's job and a woman's job as well. This change and perspective has been reflected as most social change eventually is in the jurisprudence of the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court began to look more closely at legislation providing dissimilar treatment for similarly situated women and men in the early 1970s. The first case in which the Supreme Court found a state law discriminating against women to be unconstitutional, was read versus read and read the court struck on an Idaho law giving man on automatic preference and appointments as administrators of estates read signaled automatic change in the approach of the Supreme Court to the myth of the true woman. In subsequent cases, the Court made clear that it would not only swallow unquestioningly the story that women are different in 1973, striking down a federal statute which made it easier for men to claim their wives as dependents than it was for women to claim their husbands as dependents. Justice Brennan wrote this, there can be no doubt that our nation has had a long and unfortunate history of sex discrimination. Traditionally, such discrimination was rationalized by an attitude of romantic paternalism, which in practical effect, put women not on a pedestal, but in a cage. In 1976, the Supreme Court made it smaller or full standard of review explicit ruling that sex based classifications be upheld only if they served important governmental objectives, and were substantially related to the achievement one of those objectives. Through the next two decades. The court invalidated on equal protection grounds a broad range of statutes that discriminate against women. For example, a Social Security Act provision allowing widows but not widowers to collect survivors benefit, a state law permitting the sale of beer to women at age 18, but not to man until age 21. A state law requiring men but not women to pay alimony after divorce, a social security provision allowing benefits for families with dependent children only when the father was unemployed, not when the mother was unemployed. And a state statute granting only husbands the right to manage dispose of jointly own property without the spouses consent. The volume of cases and the Supreme Court dealing with sex discrimination declined somewhat in the 1980s. Several of the more recent case is brought before the court have involved interpretations of statutes such as title seven, rather than the equal protection clause. But in all of these cases, cordis look with a somewhat jaundice die at the loose fitting generalizations, the myths and the archaic stereotypes that previously had kept women at home. Instead, the court has often asked employers to look whether the particular person at all male or female is capable of doing the job. Not quite other women in general are more or less capable than man. some measure of how far women have come since those early cases is shown by the fact that a young attorney briefed or argued most of those seminal women's rights cases, has recently become my newest colleague, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

reflecting on how difficult it was for women to break free of the traditional conception of their proper role in our society, and how essential it is that women succeed and law and other fields so they can be models for other women trying to achieve their goals. I want to read to you today, maybe more length than I normally would for letter that I recently received from one of my former law clerks. Her letter to me was occasioned by Justice Ginsburg's investiture at the Supreme Court, and this is what my former law clerk wrote. When I called your chambers yesterday, I was thinking that October 119 93, was both the Friday before the first Monday of the term, and a red letter day in its own right. I can't tell you how happy it makes me and so many others to see justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg joining you up there. Professor ginsburg actually played a key role in my life. When I began to think about law school, I didn't have a college degree, I began working like a demon to earn my college credits and the region's external degree program. I applied to all the law schools within striking distance of my home. I was admitted to a local school and to Columbia. I'm sure the only reason I was admitted to Columbia is that I talked my way into the admissions office to plead my case. I borrowed a wine colored polyester blazer with wide lapels from my friend Betty. In 1980, I was a wife and mother erstwhile were Meter Reader and nursery school teacher. I owned only blue jeans and dresses. But Betty had an authoritative series looking blazer. And because she was then juggling roles as wife, mother of three part time, registered nurse and master student and health policy at night, when I visited Columbia, it was the first time I'd ever driven into New York City and I got a parking ticket. I managed to convince the dean that I really would be able to earn the hundred and eight college credits I still needed in the next six months, and that Columbia should take a chance on me. Although he did ask how I plan to care for my children, something we would never ask a woman applicant these days. Columbia admitted me. But a local school near my home, offered me substantial financial aid. I had responsibility for children ages 610 and 11. a tight family budget and a husband who was very supportive but traveled a great deal. It made sense for me to go to a school closer to home. Besides what business that I have going to Columbia. I remember a friend said to me and my husband why spend the money for what you want to do a community college is good enough. Columbia was for real lawyers, not for housewives like me. During this period, Columbia invited all admitted students to Myra Bradwell day. Again, I borrowed the wine colored blazer, hoping to blend Dan and look like a real law student. That was the first time I saw Professor ginsburg. As I recall, she was the moderator of a panel of Columbia grads speaking about balancing career and personal lives. And what it was like to be a woman lawyer. Looking back, I appreciate how often Ruth ginsburg muffin tapped, organize or moderate a panel on women. how busy she was, and how tempting It must have been to say no, I'm grateful she did not. That panel made me actually believed I belong at Columbia. What I remember is not so much what the speakers at is the fact that they were real women. I could imagine working with them and even being like them. They were smart, serious, Frank. And just like my friends, it seemed as if they could be deeply committed to jobs and issues and still deeply committed to their children, husbands and parents. That it was all right. My husband had been encouraging me to go to Columbia. But this was the first time I really felt entitled, this year, I pay the last installment on my student loans. Everything the loans, the long commute the naked fear of flunking out was worth it. It was the beginning of refusing to allow myself to be defined by others meager expectations, and of quote,

well, what this does is to tell us that we know the power of simply seeing a woman actually doing the job. It gives people who are forming their own identities at whatever age a strength that gets passed back and forth over the years. And as as my law clerks, Bram Betty said, when she left the plate blazing, in 1980, essentially was this put this on and go out and fight for what you want. So my law clerk says that after she finished our phone conversation on the Friday before the first Monday this year, then I went into the roving room to put on my robe to prepare for Justice Ginsburg's investiture, and my Leclerc drove down Constitution Avenue, and she saw a motorcade passing by. And it was the president on his way to the court for that and better church ceremony. It was a very special day, and day that offers great hope. I think for all of us. It was a festive day. I've waited 12 years at the court, another woman justice to join me there. And I'm especially delighted that my new colleague, is both an illustrious lawyer and someone who was so influenced a younger generation of women lawyers. Now no longer will joke be. You've seen one female Supreme Court Justice, you've seen them all. The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote that now visitors to the court will have to ask, which one is Sandra Day O'Connor?

Well, I'm sure you all want to know what happened to my law clerk who was the source of this wonderful reminiscence today. Her name is Barbara Bena Woodhouse. She's here today and she's a professor at your very own university of pennsylvania law school. And following in this wonderful tradition, her daughter has recently taken the LSAT exam and applying for law school admission. Well as this story illustrates, much has been accomplished to equalize the positions of men and women in the profession of law, as well as in other fields. Never the last significant differences between men and women professionals who assist, women still have the primary responsibility for children and housekeeping, spending roughly twice as much time on these cares as do their professional husbands. As a result, women lawyers sometimes have special difficulties managing both household and a career. While many women juggle both profession and home admirably. It's nonetheless true that time spent at home is time that can't be built clients, or spent making contacts with clients or professional organizations. As a result, women may still face what has been called a glass ceiling in the legal profession, delayed or a blocked a stamp to partnership or management status due to family responsibilities. Women who don't want to be left behind sometimes are faced with hard choices is some give up family life in order to attain their career aspirations. many talented young women lawyers decide the demands of career require them to delay family responsibilities, at the very time in their lives when rearing children is physically easiest. I chose to try to have and enjoy my family and resume my career path, somewhat laser. The progress thus far of women on the law and elsewhere, is due largely to the African example of women lawyers, like Carrie Burnham Kilgore here in Pennsylvania, like Justice Ginsburg, like judge Schapiro whom we honor today, but there is still more to accomplish. I hope that the spirit of the award given today, all of you will heed these examples, and will yourselves try to achieve the goals represented by the award given today. As we face the new challenges presented by our modern era, I asked you, men and women alike, to provide guidance and encouragement to all those young people who are striving both professionally and personally and to all those who refuse to be defined by others meager expectations. Thank you.